An Analysis of Vlassis Caniaris’s Sculpture

The Child

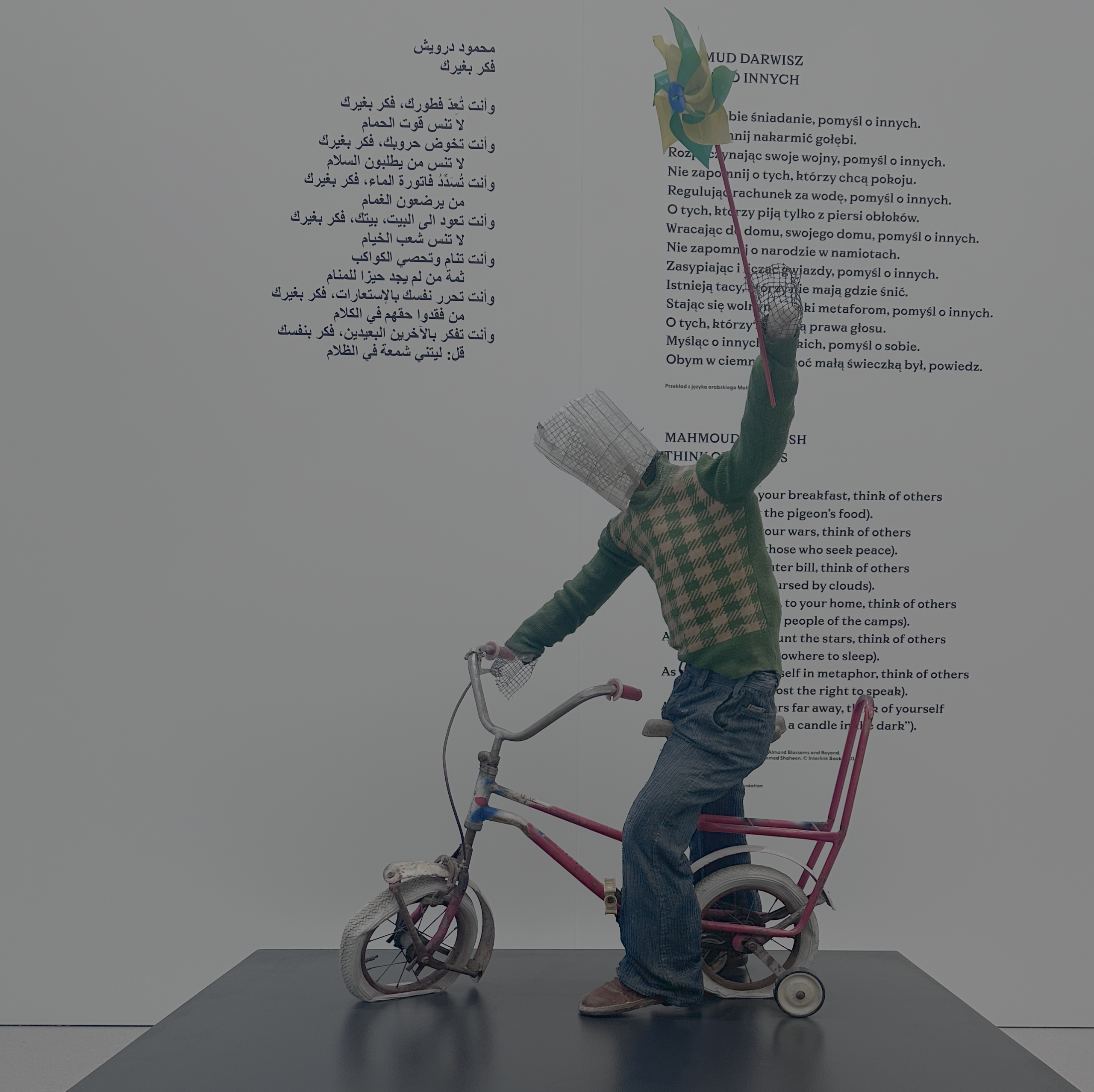

Photograph: Vlassis Caniaris, The Child (1980), Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

In contemporary art, everyday objects often transcend their original function to become carriers of powerful emotions and political meaning. One striking example is The Child (1980) by Greek artist Vlassis Caniaris, currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. At the center of this haunting installation stands an old children’s bicycle—an object normally associated with play, freedom, and growth, here transformed into a profound symbol of vulnerability, displacement, and social exclusion.

The Artist and His Materials

Vlassis Caniaris (1928–2011) was one of the most important figures in postwar Greek art. Rejecting the traditional language of sculpture, he worked with plaster, paper, wire, and found objects: worn clothes, suitcases, everyday items—and children’s toys. His practice was never about aesthetic pleasure alone. Instead, it aimed to confront viewers with social realities that are often uncomfortable, overlooked, or deliberately ignored.

By using ordinary, sometimes discarded materials, Caniaris anchored his work firmly in lived experience. His sculptures feel less like autonomous art objects and more like silent witnesses—records of human lives shaped by politics, poverty, migration, and loss.

The Symbolism of the Bicycle and the Figure

At first glance, The Child presents a simple, almost tender image: a child seated on a bicycle, holding a colorful pinwheel. Yet a closer look reveals deeply unsettling details. The child’s head is not a face at all, but a hollow metal mesh. There are no eyes, no mouth—no individuality. Identity has been erased.

The bicycle, traditionally a symbol of freedom, independence, and forward movement, is immobilized within the sculptural composition. It no longer promises escape or adventure. Instead, it becomes a fragile structure carrying the weight of a childhood shaped by forces entirely beyond the child’s control.

Migration, Childhood, and the Gastarbeiter

Caniaris devoted much of his work to the experience of migrant laborers—Gastarbeiter—in postwar Western Europe. The Child belongs squarely within this context. It reflects a reality marked by displacement, social marginalization, and economic precarity, experienced not only by workers themselves but also by their families.

Seen through this lens, the bicycle takes on a new meaning. For a migrant child, it is not merely a toy or a rite of passage. It becomes a practical tool for navigating unfamiliar streets and hostile environments, while simultaneously symbolizing stalled progress and uncertain belonging.

A Dialogue with Poetry

In the exhibition space, the sculpture appears alongside Mahmoud Darwish’s poem Think of Others. This juxtaposition intensifies the emotional resonance of the work. Darwish’s lines—urging the reader to remember those who cannot take shelter for granted, who live without stability or security—echo powerfully when set against the anonymous child on the bicycle.

In this dialogue between visual art and poetry, the bicycle ceases to be a mere object. It becomes a narrative device, binding personal vulnerability to collective responsibility, and reminding us that dignity and solidarity are inseparable.

Conclusion

An encounter with The Child at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw is a stark reminder that the bicycle in art can function as far more than an aesthetic motif. In Caniaris’s hands, it becomes a symbol of movement burdened by history, of childhood shaped by migration, and of lives lived within systems that often deny visibility and voice.

Here, the bicycle carries not just a child, but the accumulated weight of experience—an emblem of how even the simplest objects can speak with striking clarity about the human condition.